Day 10: Isurava Memorial to Hoi Village

Reveille breaks the pre-dawn silence over the valley as we rouse ourselves for a Dawn Service you will never forget.

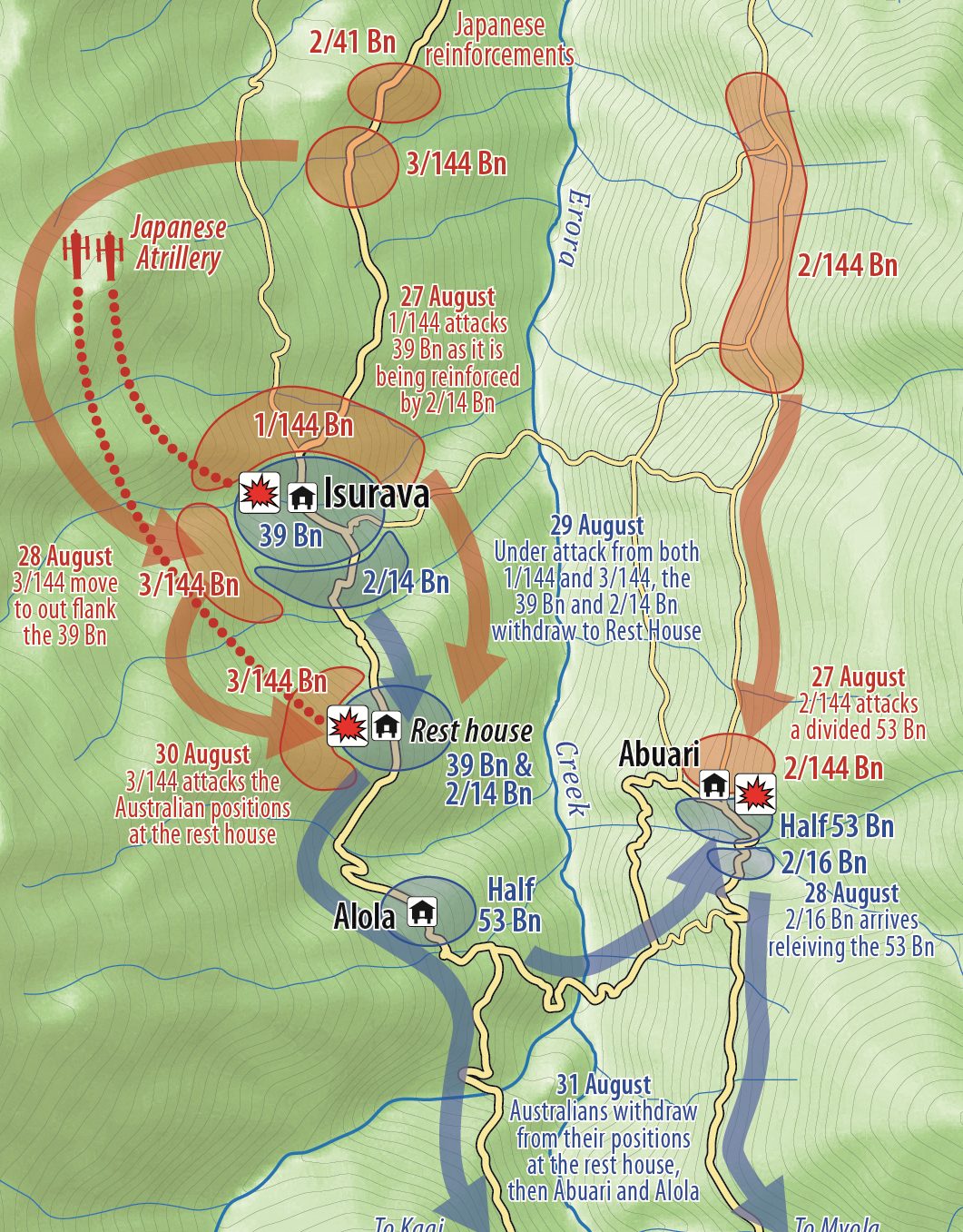

In the pre-dawn light sleepy trekkers assemble quietly at the memorial. Out of the darkness they are joined by their guides and carriers who congregate around the granite pillars as your trek leader gives a briefing on the hellfire that lasted for four days between 26 and 30 August 1942. Every human quality that makes us such a proud nation was exhibited during this epic battle.

As the Australians were withdrawing from Kokoda more of their mates from the remainder of the 39th Battalion were making their way across track to reinforce them. Among them was Lieutenant Colonel Ralph Honner who was appointed as their new commander after the death of Lieutenant Colonel Owen. Honner was an intelligent, confident, courageous and well respected leader. He had great faith in his men and they never gave him reason to doubt his judgement. He had been ordered to hold the line at Isurava whilst the brass back in Australia belatedly decided the situation was now urgent enough to get our regular troops to the front line.

So Colonel Ralph Honner drew his line in the mud of Isurava just as Colonel Travis drew his line in the sand at the Alamo 106 years earlier. Unfortunately for Honner the odds his 39th Battalion faced at Isurava were about the same as the odds faced by the Texans at the Alamo!

‘Through the widening breach poured another flood of the attackers . . . met with Bren gun and Tommy gun, with bayonet and grenade, but still they came, to close with the buffet of fist and boot and rifle-butt, the steel of crashing helmets and of straining, strangling fingers. In this vicious fighting, man-to-man and hand-to-hand. Merrit’s men were in imminent peril of annihilation.’[i]

Our young warriors did not yield against the odds they faced during the hour of their peril. As the battle raged there were so many acts of courage and self-sacrifice that it is impossible to acknowledge them all. Even so the battle was to yield more Allied decorations than in any other single battle in the Pacific:

‘These were not blind heroics; they were calculated initiatives by Australian privates, corporals and platoon commanders determined to hold off the enemy as their units withdrew. Thus Private Wakefield, a Sydney wool worker, held up a Japanese charge as his section fell back; he won the Military Medal. Thus Captain Maurice Treacy, a shop assistant, ‘parried every thrust levelled at him’[ii]. He got a Military Cross. Though wounded in the hand and foot, Corporal ‘Teddy’ Bear, a die-cast operator from Moonee Ponds, killed a reported’15 Japanese with his Bren gun at point blank range’; he was later awarded the Military Medal and the DCM.[iii] Lieutenant Mason, a draughtsman, led his platoon in four counterattacks that afternoon; as did Lieutenant Butch Bissett, a jackeroo, whose platoon fought off fourteen Japanese charges.’[iv]

As the fate of the battalion hung in the balance a young Australian, Private Bruce Kingsbury, seized the initiative:

‘. . . He rushed forward firing his Bren light machine-gun from the hip, through terrific machine-gun fire, and succeeded in clearing a path through the enemy for the platoon; a courageous action which made it possible for us to recapture the position. He continued on, still sweeping the enemy positions with his Bren light machine-gun and inflicting an extremely high number of casualties on the enemy, but he was killed by a sniper hiding in the timber.’

.jpg)

Private Bruce Kingsbury, age 24, was posthumously awarded the first Victoria Cross won on Australian territory.

Whilst the Australians suffered a tactical defeat their heroic stand against overwhelming odds caused the Japanese to suffer unacceptable casualties and use up valuable stocks of ammunition and supplies.

‘What made Isurava uniquely wretched in the annals of war was the devastating closeness of combat. The armies were fighting within earshot and, unlike their medieval forebears, with guns and grenades. ‘When the Japs were about ten feet away . . . I shrivelled up into almost nothing,’ recalled one private. Near the end of the Pacific War a US army medical team examined the effects of near point-blank fighting in jungle conditions. It found that more than 50 per cent of the casualties were struck at 25 yards or less, and nearly 85 per cent at 50 yards or less[v]. The wounds inflicted by a high velocity bullet at this distance can be imagined. Abdominal injuries were always fatal; shattered knees and limbs left the victim stranded. There were no helicopters. Hand-to-hand combat with fixed bayonets made the battle seem like ‘a knife fight out of the Stone Age’[vi].[vii]’

At the conclusion of the presentation your trek leader will conduct a Dawn Service that will live in your memory forever. Your guides and carriers provide a memorable finale as they sing a traditional songs and the PNG national anthem in exquisite harmony.

‘It is as if we have arrived. Somewhere, anywhere. Our guides sit with us, their families join us, and the village and its people become imprinted in our hearts. Another woman and I join the evening church service and are entranced as the pastor, his face illuminated by a hurricane lamp, recites the prayers in pidgin and the children’s voices rise in harmony so sweet we never want it to end’.[viii]

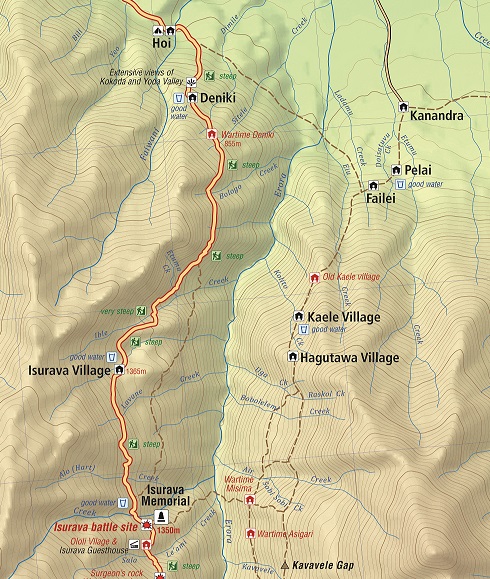

We return to our campsite for breakfast then continue our trek along the ridge via numerous creeks – Alo, Nobogolo, Kimaea, Kukuve and Subile for an hour until we enter Isurava village at 1,360 meters AMSL which was re-located to this site after the war.

After morning tea we begin our trek down Luboi Ridge towards the abandoned wartime village of Deniki at 865 meters AMSL via Ilole, Etume, Borogo, Botolo, and Selele creeks. A feature of our trek down the ridge is the number of abandoned native gardens that have been overgrown with choko vines. The 39th battalion fought a short but ferocious battle at this wartime position Deniki before being forced further back along the trail to Isurava.

A short distance further on we arrive at our lunch spot at Deniki (805 meters AMSL) where a couple of huts have recently been built to cater for trekkers. There are extensive views down the Yodda valley to Kokoda from here. ‘Foku’ is the local name for the area which has Okari trees (with edible nuts) on the site.

After lunch we have a short 20 minute trek down to our campsite on a creek at Hoi village which is 505 meters AMSL. The locals usually provide a feast of fresh coconuts, papaya, bananas, pineapple and fresh scones. Hoi is known for its beautiful butterflies by day and its fireflies which light up the campsite at night.

[i] The 39th at Isurava. Australian Army Journal, July 1967. Ralph Honner

[ii] South-West Pacific Area-First Year, Kokoda to Wau. Dudley McCarthy p. 207

[iii] Ibid. p.206

[iv] Kokoda by Paul Ham. p.175

[v] Touched with Fire: The Land War in the South Pacific. E Bergerud. Viking, New York. 1996 p.285

[vi] Ibid p. 285

[vii] Kokoda by Paul Ham p. 181

[viii] Hard Slog to Kokoda. Canberra Times, 15 November 1992 by Marion Smith who trekked with Charlie Lynn earlier that year.

Why Trek with Adventure Kokoda

Our primary goal is to lead you safely across the Kokoda Trail and ensure you have an unforgettable wartime historical and cultural experience.

Charlie has led 101 expeditions across the Kokoda Trail over the past 32 years.

He previously served in the Australian Army for 21 years. During this time he saw active service in Vietnam; was assigned to the joint Australian, New Zealand and British (ANZUK) Force in Singapore/ Malaysia from 1970-72, and as an exchange instructor in Airborne Logistics with the United States Army from 1977-78. He is a graduate of the Army Command and Staff College.

.JPG)