Before time . . .

Mystery clouds the human story of New Guinea and the origins of the vast majority of the people who now inhabit it. No one can say for certain whence or when they came, but the probabilities are that the big island and its smaller neighbours were colonised by successive waves of migrants from lands to the north and west.

The first men in New Guinea may well have been ethnic cousins of the aborigines of Australia, the Dravidians of  India and the Sakai people of the highlands of Malaya. They arrived when there still land links between New Guinea and parts of Asia. They were eventually displaced or absorbed by newcomers who also crossed before the land bridge disappeared. Just when the migrations began and over what period they extended is at present an exciting guessing game for ethnologists. In time, scientists may collect enough information to change speculation into accurate deduction, but probably the pioneers were a woolly-haired Negrito or pygmy type believed to have originated in Malaysia or Indonesia.

India and the Sakai people of the highlands of Malaya. They arrived when there still land links between New Guinea and parts of Asia. They were eventually displaced or absorbed by newcomers who also crossed before the land bridge disappeared. Just when the migrations began and over what period they extended is at present an exciting guessing game for ethnologists. In time, scientists may collect enough information to change speculation into accurate deduction, but probably the pioneers were a woolly-haired Negrito or pygmy type believed to have originated in Malaysia or Indonesia.

The next waves of immigrants are thought to have been tall dark-skinned, curly-haired negroid people with prominent noses who were classed thirty years ago as ‘true Papuans’.

In the third migratory wave were the Melanesians – a vigorous, seafaring people who, in their wanderings over the Indian and Pacific Oceans by outrigger canoe, had picked up by intermarriage a confusion of physical traits including while range of skin tints and some resemblance to both the mongoloid races of South-East Asia and the negroes of West Africa. They almost certainly arrived after the bridge with Asia had been cut.

The three basic racial types did not, however, remain separated. They intermarried by some degree and thus acquired such an extraordinary mixture of race characteristics that it is difficult today to say any one New Guinea tribe is predominately Melanesian, Papuan or Negrito. The ethnological picture has been further confused by the discovery in recent years of tall, light-skinned, mountain people who don’t seem to fit at all into any combination of Melanesian, Papuan and Negrito.

The peoples of New Guinea are not, therefore, of any fixed, definable type. They are an almost incredible agglomeration of racial types which have remained only imperfectly mingled because of the extreme difficulty of moving about freely in the New Guinea terrain. Thus a New Guinea native’s skin can be any colour from pale biscuit brown to blue black. His hair can be almost straight, woolly, frizzy, curly or wavy. His natural stature can range from a strapping six-foot to a freakish four foot three inches. The shape of his nose can be flat, semitic, straight or aquiline. And he can be round-headed, broad-headed or long-headed. At the extremes of difference one New Guinea tribesman can be as unlike another as an Eskimo is unlike a Hottentot, or a Laplander unlike a Sicilian.

The almost limitless variety of physical dissimilarities is paralleled by language differences. In the Australian half of the island, more than 500 mutually unintelligible languages have been officially listed among a population of about 2,000,000 – and the list is growing in the last areas unknown to Europeans are being explored. Before the Dutch handed over West New Guinea to Indonesia in 1963, they had listed in their territory more than 200 languages among about 500,000 people of a total population estimated at 700,000.

In coastal regions it is rare for tribal groups speaking a common language to number more than 5,000 people – although the Tolai language of the Gazelle Peninsula of New Britain is no spoken by about 40,000. In the more densely populated highland valleys, however, there are several language groups numbering more than 30,000 – but in the most rugged and inhospitable regions tribes of a few hundred have a distinct language of their own and no knowledge of any other.

The Spirit World . . .

The primitive religions of all the diverse New Guinea tribes are fundamentally similar. They believe that the affairs of this world and the lives of the people in it are very largely managed by the inhabitants of a spirit world. The inhabitants of the spirit world are various – sometimes of superhuman extra-terrestrial origin, sometimes superhuman but terrestrial, but more often simply that ghosts of the dead. All the tribes seem to ascribe to the individual soul persistence, either permanent or impermanent, after physical death. Furthermore, all the tribes seem to believe that communication between the material and spirit world is possible in a number of ways, and that the behaviour of the spirits can be influenced by the behaviour of living people. There is also a practically universal belief that some spirits are good and friendly, others are bad and unfriendly, and all spirits can be placated, propitiated or circumvented by ritual actions.

Close resemblance between tribal or regional religion does not go much deeper than this; but a great majority of the people believed, and indeed still believe, that accident, illness, death, defeat in combat, and such disasters as freakish floods or crop failures, are caused by the intervention inhuman affairs of hostile supernatural forces. Since the actions of living people affect the actions of the spirits, a man’s enemies are primarily responsible through the agency of sorcerers or magic rituals for the ills that befall him. The primitive New Guinean believed absolutely that systems of efficacious sorcery and magic (and of counter-sorcery and counter-magic) were necessary for survival. Without that belief, the paradoxes of his environment would have confounded him utterly.

Discovery . . .

Except for the Amazonian province of Brazil, New Guinea resisted European penetration longer than any other habitable region of its size on earth. The maze of offshore reefs and shoals made its approaches perilous for all but the most skilled seafarers in the smallest of landing craft, its terrain blocked efforts to explore the hinterland, and the reputation of its savage tribesmen was so forbidding that even the treasure-hunters of the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries gave it a wide berth.

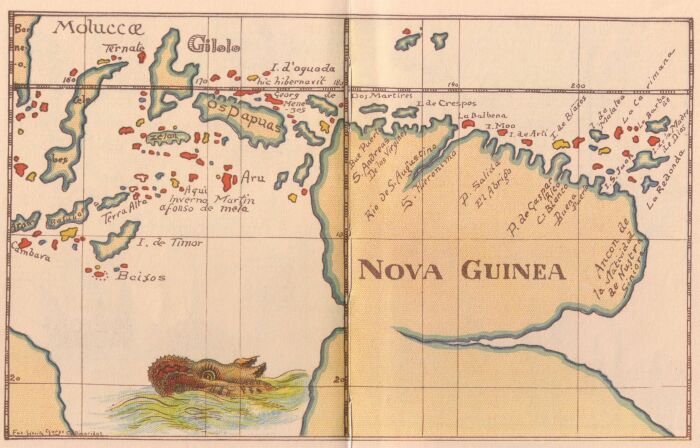

Historians believe that the two Portuguese navigators, Antonio D’Abreu and Francisco Serrano, were the first  Europeans to sight the mainland in 1512 on a voyage of exploration from the East Indies. In 1526-7 another Portuguese, Jorge de Meneses, looking for route from the Malay Peninsula to the Spice Islands, landed on the shores of western New Guinea and called it ‘Ilhas dos Papuas’ – the land of the frizzy haired people. Ten years later the crew of a Spanish ship out of Peru mutinied and murdered their captain, Hernando de Frijalva, shortly before the ship was wrecked somewhere on the north coast. They were taken prisoner by the natives and those who survived were liberated after years by Portuguese traders from the Celebes. In 1545 Ynigo Ortiz de Retez, a Spaniard from tidore, landed in the extreme west and claimed possession for his country of the territory which was later to become Dutch New Guinea. He named the place New Guinea because he thought it resembled the Guinea Coast in West Africa. But Spain made no attempt to consolidate Retez’s claim.

Europeans to sight the mainland in 1512 on a voyage of exploration from the East Indies. In 1526-7 another Portuguese, Jorge de Meneses, looking for route from the Malay Peninsula to the Spice Islands, landed on the shores of western New Guinea and called it ‘Ilhas dos Papuas’ – the land of the frizzy haired people. Ten years later the crew of a Spanish ship out of Peru mutinied and murdered their captain, Hernando de Frijalva, shortly before the ship was wrecked somewhere on the north coast. They were taken prisoner by the natives and those who survived were liberated after years by Portuguese traders from the Celebes. In 1545 Ynigo Ortiz de Retez, a Spaniard from tidore, landed in the extreme west and claimed possession for his country of the territory which was later to become Dutch New Guinea. He named the place New Guinea because he thought it resembled the Guinea Coast in West Africa. But Spain made no attempt to consolidate Retez’s claim.

During the next three hundred years practically every great maritime explorer of the Indian and Pacific Oceans touched New Guinea and mapped parts of its coast. Torres discovered the Loiisiade group and charted Milne Bay and parts of the north-east coast in 1605. Jansz, Le Maire and Willem Schouten made voyages along the north coast. In 1642 Abel Tasman reported that he believed the island had agricultural and trading possibilities. Will Dampier named New Britain in 1700. Cartaret, Bougainville, Cook, Hunter and McCluer all sighted and examined sections of the New Guinea coast and filled in blank spots on the charts of their times. But it was not until 1793 that the British East India Company, acting on a report by McCluer that there were possibilities for the spice trade east of the Moluccas and Ceram, made a half-hearted attempt to establish a settlement on Geelvink Bay. Captain John Hayes, in the warship Duke of Clarence, raised the flag at Restoration Bay and built a small fort which he named New Albion, but the annexation was never confirmed and the post soon abandoned. For political reasons the British decided to allow the Dutch a free hand in the area, and in 1814 recognised the ancient claim of the Sultan of Tidore to overlordship of the West New Guinea tribes. As the Sultan himself owed allegiance to the House of Orange, this was tantamount to ceding sovereignty to the Dutch, but it was a surrender of small significance in those days.

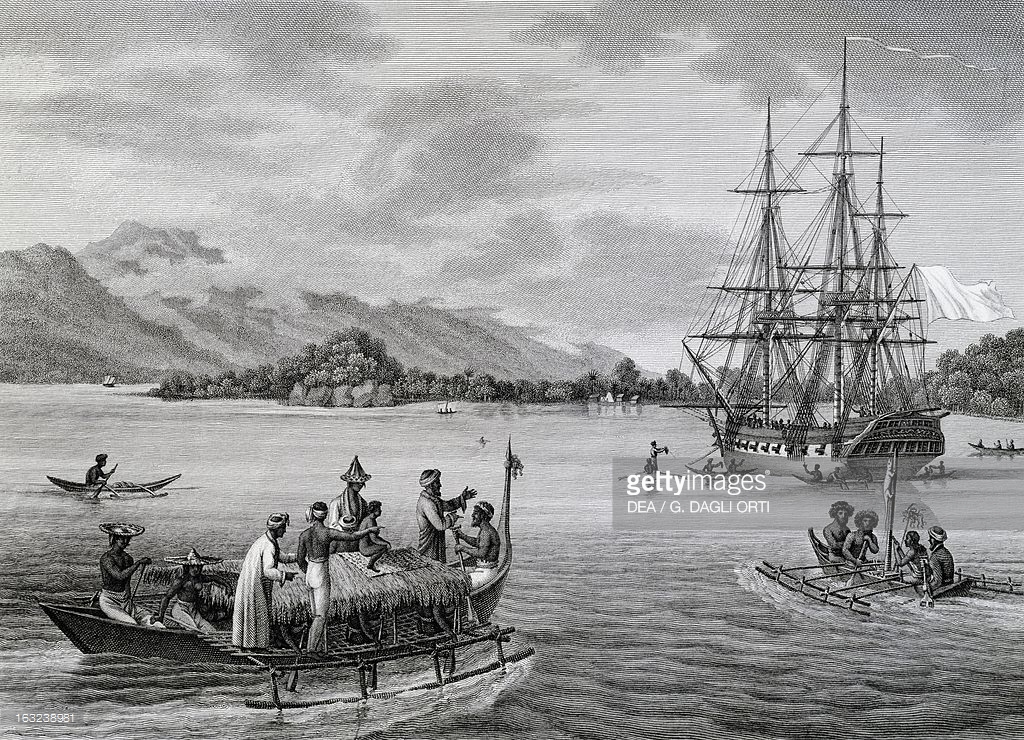

Tidore’s claims to rule West New Guinea dated back to the thirteenth or fourteenth century, but with little practical substance. A few Indonesian sailing canoes had irregular contact with Papuan coastal communities in the western half of the island, but at no time were those communities brought under powerful or permanent Indonesian influence, and much less were they conquered or governed by the agents of the Sultanate. New Guinea and its people were a combination which for hundreds of years resisted the expansionism of both East Indian princelings and European empire builders alike. Until the middle of the nineteenth century even the coastal tribes had little contact with the outside world of either East or West, and the inland tribes had virtually no contact at all.

The first white men to seek prolonged contact with coastal New Guineans were not explorers but maritime traders based in Australia. By the middle of the nineteenth century small sailing vessels, usually out of Sydney or Auckland, were making more or less regular expeditions to the Solomon Islands and New Guinea. It was a time of rapid commercial expansion in Oceania. The colonial empires of the British, Dutch and French were well established in Asia and Australasia, and the Americans were colonising and developing their own West Coast. The Pacific Islands had become the new frontier – a frontier pioneered, as usual, by individualists who were rugged indeed and who sought fortune and freedom beyond the ordered preserves of the great trading companies.

In 1870 a naturalist, Richard Daintree, submitted to the Ministry of Public Works in Queensland a paper suggesting that the gold-bearing structures in North Queensland continued across the Coral Sea and would be encountered again in south-east New Guinea. Three years later the observations of Captain Moresby indicated that such a geological continuity did, in fact, exist. In 1877, a discovery of trace gold near the future site of Port Moresby started a minor rush of excitable prospectors who were soon to regret their rashness in challenging a country far more formidably hostile than north Queensland. None found gold in payable quantities. Many died of malaria and exposure or were murdered by the natives.

Colonization . . .

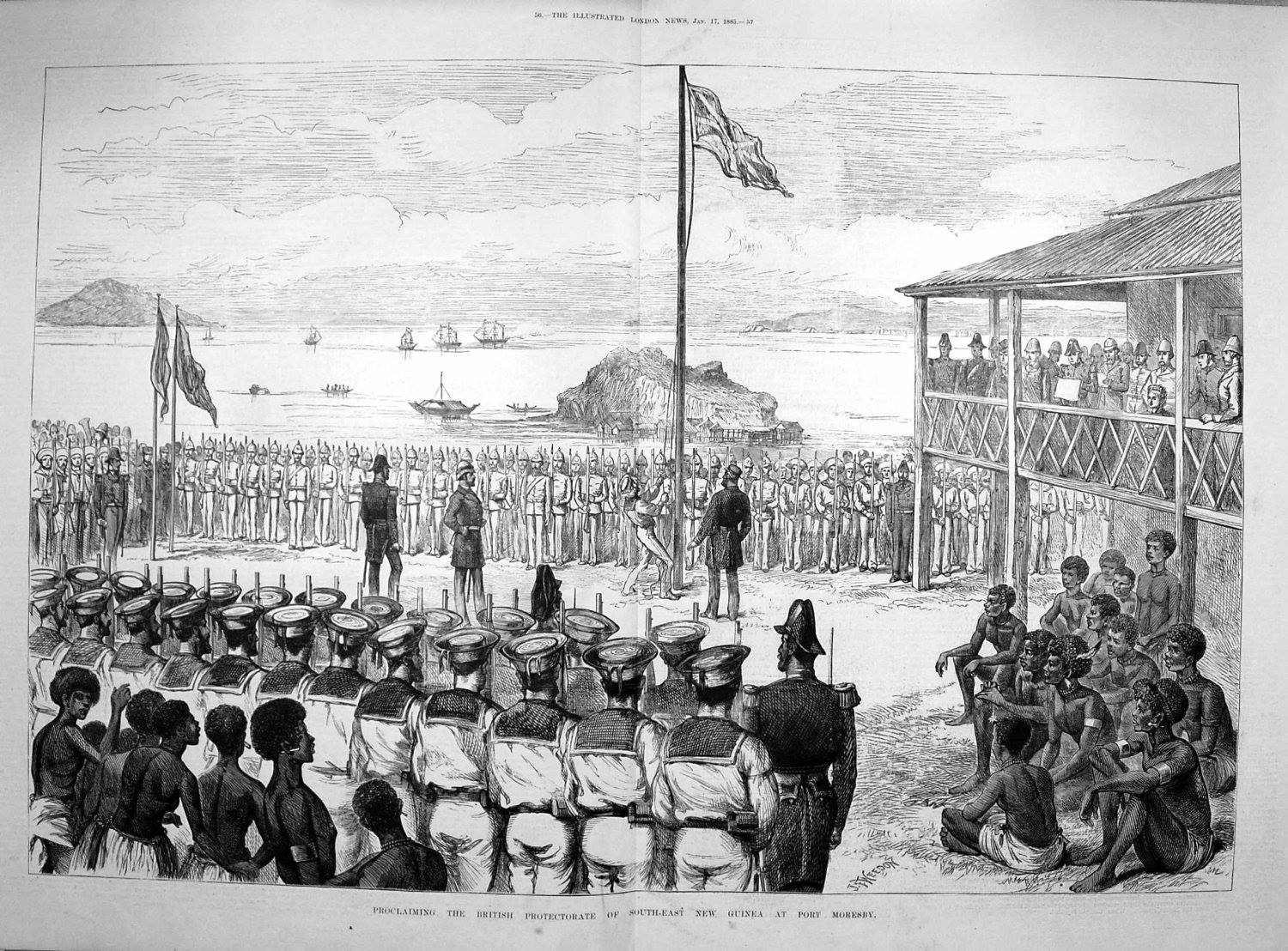

The colonial powers of France, Holland, Germany and Britain were increasing the interest and influence in the Pacific. The Queensland Government was increasingly alarmed by rumours that the Germans planned a land grab in New Guinea, and early in 1883 the Premier, Sir Thomas McIlwraith, instructed the Resident Magistrate on Thursday Island, Mr H.M. Chester, to annex the Easter half of the mainland in the name of the British Crown. This Chester did on 4 April 1883, at Port Moresby; but the British Government promptly repudiated the action. It wanted no further expansion of the Empire that might precipitate trouble with Germany and it was doubtless influenced by the opinion of the pioneer missionaries, Lawes and Brown, that Queensland’s interest in annexation largely stemmed from a desire to ensure continuity of recruited labour for the northern sugar and cotton plantations.

There was immediate and excited reaction in the colonies to the British Government’s repudiation. In November and December 1883, an Intercolonial Convention in Sydney unanimously urged the United Kingdom to annex New Guinea and agreed to contribute £15,000 a year to the cost of administration. This time the colonies’ clamour was too loud and angry to be pigeon-holed. In August 1844 the British and German Governments held informal discussions and Britain announced that it would declare a protectorate over the territory lying between the agreed Dutch boundary and the 145th meridian. Germany protested strongly, and the British accordingly agreed to confine their claims to the south coast. On 6 November, Commodore J.E. Erskine declared the British protectorate. Ten days later Germany proclaimed its protectorate, naming the whole of the north coast and the islands of the Bismark Archipelago. It was Britain’s turn to protest and Germany compromised by setting its boundary at the 148th meridian on the north coast of the island. Island frontiers between the two protectorates were later negotiated and the partition was ratified by treaty in June, 1885.

Australian reaction to these arrangements was again antagonistic. The States were agitated because Germany had now gained a footing in the strategic area and felt that Britain had been humiliatingly outsmarted – at the cost of Australian security. For the first time the Pacific colonies were solidly unified in disapproval of British policy and some historians see here the germ of the federation of the Australian States achieved about twenty years later.

At long last the occupation of the Pacific no-man’s-land by Europeans was a political and legal reality, but many years were to pass before political and legal reality had much practical effect on the majority of the native inhabitants.

It should be remembered that the complexity of events leading up to the establishment of the British and German protectorates in New Guinea did not in any sense imply that there was already massive contact between native and European as there had been in Oceania. Some thousands of coastal tribesmen had been affected by the activities of a handful of white traders, recruiters and missionaries but there were hundreds of thousands inhabiting the hinterland who were untouched. This is an important fact to bear in mind when evaluating the early European influence. A large proportion of the mainland population was not to experience white civilization for more than seventy years after the proclamation of the protectorates.

Independence . . .

The formal path to independence began in 1964 with the establishment of a House of Assembly with 64 members. This was followed by internal self-government in 1973 and full independence on 16 September 1975.

Today . . .

Today PNG has a population of 7.5 million people with a population growth rate of 1.75 percent. The country is rich in resources but lies at the bottom of the scale on international social indicator rankings[i]:

- The University of PNG is ranked 5168 in the world (ANU: 19)

- Birth rate: 24 births/per 1,000 population (Australia: 12.1)

- Death rate: 6.5 deaths/1,000 population (Australia: 7.2)

- Maternal Mortality Rate: 215 deaths /100,000 live births (Australia: 6)

- Infant Mortality Rates: 37.4 deaths/1,000 live births (Australia: 4.3)

- Life Expectancy: Male 65 years – Female 69.5 years Australia: 79.8 and 84.8)

- Total Fertility Rate: 3.1 children born/woman (Australia: 1.77)

- Physician Density: 0.06 physicians per 1,000 population (Australia: 3.27)

- Children under age of 5 underweight: 27.0 percent (Australia: 0.2 percent)

- Literacy (age 15 and over who can read and write): 64.2 percent

- Population below the poverty line: 37 per cent (Australia: 12 percent)

According to the 2016 Oxford Business Report:

‘Culturally one of the world’s most diverse countries, Papua New Guinea is widely considered to be one of the last frontiers for tourism and business opportunities – the island of New Guinea hosts 6-8% of the world’s species, one-sixth of known languages and rivals Borneo, the Amazon and the Congo in terms of biodiversity. The country is an important exporter of natural resources (gold, copper, oil and natural gas) as well as agricultural products, with its cash crops including coffee, oil palm, cocoa, coconut and to a lesser extent tea and rubber. PNG also became a major exporter of natural gas in 2014, significantly increasing the size and strength of its economy, and the $19bn PNG Liquefied Natural Gas project was completed ahead of schedule and within budget.

‘The economy of Papua New Guinea is decelerating, with the GDP growth rate expected to fall by half in 2016 to 4.3% and by nearly half again to 2.4% in 2017. A combination of the end of the construction phase of the PNG Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) project and an unexpected drop in energy prices has resulted in a significant decline in business activity and state revenues. The PNG economy is in for a rough few years as it adjusts to the drop in LNG prices and awaits the start of the next major project. However, barring any further dramatic declines in energy prices, growth will remain positive and the government will be able to bring its spending closer in line with revenues.’

Papua New Guinea is the last adventure – a land of the unexpected within a parliament of a thousand tribes. It is a land of fascinating cultures, breathless landscapes and some of the friendliest people in the world. The most common observation from young Australians who have shared the pilgrimage across the Kokoda Trail with them is – ‘they have nothing but they have everything!’

They have uninhibited humour, provide unconditional care and sing with a harmony that stays in your head for months.

Recommended Reading List:

Orokaiva Society

F.E. Williams. Oxford University Press, 1930

Savages in Serge

J.G. Hides. Angus and Robertson. 1938

Drama of Orokaiva: The Social and Ceremonial Life of the Elema

F.E. Williams B.Sc. Oxford at the Claredon Press. 1940

Prowling through Papua

Frank Clune. Angus and Robertson. 1943

The Papuan Achievement

Lewis Lett. Melbourne University Press. 1944

Papua: Its people and its promise - past and future

Lewis Lett. F.W. Cheshire Melbourne. 1944

New Guinea and Australia

John Wilkes. Australian Institute of Political Science. 1958

Doctor's Wife In New Guinea

Margaret Spencer. Angus and Robertson. 1959

Patrol into Yesterday: My New Guinea Years

J.K. McCarthy. F.W. Cheshire. 1963

New Guinea: The Last Unknown

Gavin Souter.Angus and Robertson. 1963

Parliament of a Thousand Tribes

Osmar White. The Bobbs-Merrill Company Inc 1965

Assignment New Guinea

Keith Wiley. The Jacaranda Press. 1965

Justice Versus Sorcery

Justice R.T. Gore, CBE. The Jacaranda Press,1965

The Lineage System of the Mase-Enga of New Guinea

M.J. Meggitt. Oliver & Boyd, Edinburgh, London. 1965

The New Guinea Villager: A Retrospect from 1964

C.D. Rowley. F.W. Cheshire Melbourne Canberra Sydney. 1965

Time Now - Time Before

Osmar White. Heinemann London Melbourne. 1967

Hubert Murray: The Australian Pro-Consul

Francis West. Oxford University Press, 1968

New Guinea: Our Nearest Neighbour

J.K. McCarthy. Cheshire. 1968

Fashion of Law in New Guinea

B.J. Brown. Butterworths Sydney Melbourne Brisbane. 1969

New Guinea: Problems & Prospects

Peter Hastings. Cheshire, 1969

New Guinea Journeys

Jack McCarthy. Rigby. 1970

The Blackbirders: The Recruiting of South Seas Labour for Queensland 1863-1907

Edward Wyberg Docker. Angus and Robertson. 1970

Selected Letters of Sir Hubert Murray

Francis West. Oxford University Press. 1970

The Politics of Dependence

A.L. Epstein, R.S. Parker and Marie Reay. Australian National University Press. 1971

Exchange in the Social Structure of the Orokaiva

Erik Schwimmer. C. Hurst & Co, London. 1973

Readings in New Guinea History

B. Jinks, P. Bishop, H. Nelson. Angus and Robertson. 1973

Anthropology in Papua New Guinea

Ian Hogbin. Melbourne University Press. 1973

Beyond the Village: Local Politics in Madang

Louise Morauta. The Athlone Press, London. 1974

Papua New Guinea: Moment of Truth

Ian Todd. Angus & Robertson. 1974

Papua New Guinea Portaits: The Expatriate Experience

James Griffin. Australian National University Press, 1978

The Leaders and the Led: Social Control in Wogeo, New Guinea

Ian Hogbin. Melbourne University Press. 1978

Oral Traditions in Melanesia

Donald Denoon and Roderic Lacey. 1981

Taim Bilong Masta: The Australian Involvement with Papua New Guinea

Hank Nelson.ABC Books. 1982

Kiap

James Sinclair. Pacific Publications, 1981

Pathways to Independence: Story of Official and Family Life in Papua New Guinea From 1951-1975

Rachel Cleland. Self-Published. 1984

First Contact: New Guinea Highlanders Encounter the Outside World

Bob Connolly & Robin Anderson. 1987

Sorcerer and Witch in Melanesia

Michele Stephen. Melbourne University Press. 1987

Last Frontiers: The Explorations of Ivan Champion of Papua

James Sinclair. Pacific Press. 1988

Queen Emma: The Samoan-American Girl Who Founded an Empire in 19th Century New Guinea

R.W. Robson. Robert Brown & Associates. 1994

Missionaries, Headhunters & Colonial Officers

Peter Maiden. Central University Press. 2003

Black Harvest: Warfare, film-making and living dangerously in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea

Bob Connolly. ABC Books . 2005

A Short History of Papua New Guinea

Professor John Dademo Waiko. Oxford University Press. 2007

Tales of Papua New Guinea

Retired Officers Association of Papua New Guinea. 2001

Building a Nation in Papua New Guinea: Views of the Post Independence Generation

David Kavanamur, Charlies Yala and Quinton Clements. The Australian National University. 2003

[i] CIA Country Year Book – PNG and Australia

Why Trek with Adventure Kokoda

Our primary goal is to lead you safely across the Kokoda Trail and ensure you have an unforgettable wartime historical and cultural experience.

Charlie has led 101 expeditions across the Kokoda Trail over the past 32 years.

He previously served in the Australian Army for 21 years. During this time he saw active service in Vietnam; was assigned to the joint Australian, New Zealand and British (ANZUK) Force in Singapore/ Malaysia from 1970-72, and as an exchange instructor in Airborne Logistics with the United States Army from 1977-78. He is a graduate of the Army Command and Staff College.